Critical Minerals policy-wonks: if you wagered that Rare Earths would be the leading elements in the Biden 100-Day Report in terms of mentions, you’d be wrong.

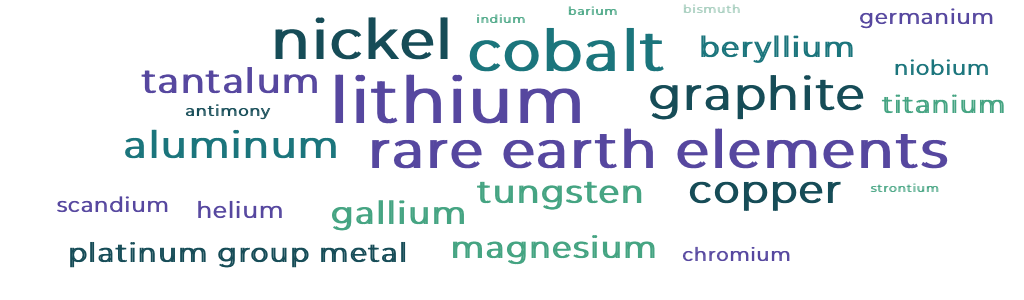

That’s right — we took a look at the Biden Administration’s just-released 100-day supply chain assessment, and created a word cloud based on the number of mentions (footnotes included) of the metals and minerals that made the official U.S. Government Critical Minerals List of 2018 — and the two that didn’t but should have (Nickel and Copper).

Here’s what it looks like:

It may come as no surprise that Lithium and Cobalt are prominently featured (Lithium is mentioned 315 times and Cobalt appears 167 times) — after all we find ourselves in a “battery arms race.”

It may come as no surprise that Lithium and Cobalt are prominently featured (Lithium is mentioned 315 times and Cobalt appears 167 times) — after all we find ourselves in a “battery arms race.”

And, of course, the Rare Earths made the cut with 105 mentions[1], but what may surprise you is that Nickel — a non-Critical, at least in terms of the official U.S. Government Critical Minerals List of 2018 – takes the bronze with a whopping 146 references. And fellow non-Critical Copper also racks up a Top Ten appearance, with 29 references.

In the Department of Energy-led supply chain assessment chapter, DoE notes under the Nickel sub-header for “Mapping the Supply Chain” that “if there are opportunities for the U.S. to target one part of the battery supply chain, this would likely be the most critical to provide short- and medium-term supply chain stability.”

DoE continues:

“In contrast to cobalt, nickel content per battery will increase in the coming years, as R&D focused on high-nickel in cathodes has shown significant and accelerated commercial adoption. The potential shortfall from this increase in demand poses a supply chain risk for battery manufacturing globally, not just in the United States; given the pervasive need, the established nickel industry is ramping up production and processing, and the United States is falling further behind China in this critical material.”

Copper is highlighted in the 100-Day Report as an integral component of Lithium-ion battery technology, in the context of being what we have called a “gateway metal” to other critical materials, and for its “use across many end-use applications aside from lithium-ion cells, including building construction, electrical and electronic products, transportation equipment, consumer and general products, and industrial machinery and equipment.”

ARPN followers can claim an I-told-you-so here. After all, ARPN’s Daniel McGroarty urged the U.S. Government to include both Nickel and Copper in the 2018 official government list of critical minerals in his Public Comment submission.

With that brief moment of vindication, let’s move on to say that the Biden Administration is right to give prominence to Nickel and Copper in its strategy.

As Reuters’s Andy Home points out,

“Nickel isn’t on the U.S. list of critical minerals. Although the country depends on imports, 68% of supplies come from what the report calls “allied nations” such as Canada, Australia, Norway and Finland.

But the Department of Energy (DOE) has identified Class 1 nickel, the type best suited to lithium-ion batteries, as both a key vulnerability and key opportunity. (…)”

As the White House 100-Day Report notes:

“Eagle Mine is the only active nickel mine in the U.S. today, and its lifetime is set to end in 2025.”

Home acknowledges this fact and continues:

“There is no domestic nickel processing capacity outside a limited amount of by-product salt production.

Yet this particular battery metal is the one likely to experience the most significant demand increase over the coming years, the report says, with ‘market indications that there could be a large shortage of Class 1 nickel in the next 3-7 years.’

Indeed, with nickel content rising in battery cathode design, not having enough of the right kind of nickel ‘poses a supply chain risk for battery manufacturing globally, not just in the United States.’”

For Copper, one need to look no further than the latest IEA report which estimates that, driven by the Electric Vehicle revolution, copper demand will be 25 times greater in 2040 than it was in 2020.

Thankfully, the U.S. does not have to look far for opportunities to strengthen our position for both Nickel and Copper. The Tamarack Nickel project in Minnesota hosts a high-grade Nickel deposit, along with Copper and Cobalt as co-products. As for Copper, several of our recent posts provide an insight into domestic opportunities.

As the Department of Energy concludes:

“The United States must adopt a set of tools to increase domestic battery manufacturing while improving the resilience of the lithium battery supply chain, including the sourcing and processing of the critical minerals used in battery production.”

It’s a behemoth task, but, the good news is that in light of the United States’ mineral riches and technical knowhow the “All of the Above” approach embraced in the Biden Administration’s strategy can start at home.

[1] For the purpose of this word cloud, we counted all mentions of “Rare Earth(s)” as a group in both text and footnotes. We did not include mentions of the individual rare earth elements with the exception of Scandium, which is also treated separately by the 2018 official U.S. Government list of 35 critical minerals. Note that our word cloud generator left off several of the 35 critical minerals because they were either not mentioned at all or received very few mentions.