The coronavirus pandemic and associated supply shocks, surging demand for critical minerals against the backdrop of an accelerating global push to net zero carbon emissions, as well as rising geopolitical tensions on the heels of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the looming tech war between China and the West have catapulted the issue of securing critical mineral supply chains to top of policy agendas around the globe.

Concerns over China’s dominance over a large majority of the key critical mineral value chains has spurred efforts to decouple supply chains from China all over the globe.

Followers of ARPN are aware of U.S. efforts which include the invocation of the Defense Production Act for several critical minerals, the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act and partnership agreements with key allies as well as public-private partnership to bolster domestic critical mineral supply chains.

In Europe, the January 2023 announcement of the discovery of one of the largest rare earth elements (REE) deposits in Europe in the Kiruna mine located Sweden’s Lapland region was hailed by some as the advent of a new dawn for European resource policy, and European Union stakeholders hope that the recently released Critical Raw Materials Act, if passed, will jump start the reshoring process and “de-risk” the regional bloc’s reliance on China by streamlining the permitting process for raw materials projects and allow for selected “Strategic Projects” to benefit from support for access to financing and shorter permitting timelines.

However, as Luke Patey outlines in a piece on the European REE supply chain push for the China-focused online magazine The Wire, the process of “decoupling” is fraught with more significant real-world challenges than some would have thought considering the complexity of critical mineral supply chains, and especially REE supply chains.

For all the upbeat coverage of the Kiruna mine’s new deposit, Patey points to observers in the industry who are more cautious noting that China has “invested tens, if not, hundreds of billions of dollars in research and production to build up its industry over many years,” and cautioning that finding the REE deposits is “just step one.”

As he writes, “[t]he EU now faces the meticulous task of ticking off all nodes of the supply chain to turn its green aspirations into an industrial reality” – from mine to manufacturing – and the midstream steps of building out processing capacity, metallization and magnet making are all “steps that the EU is sorely lacking in.”

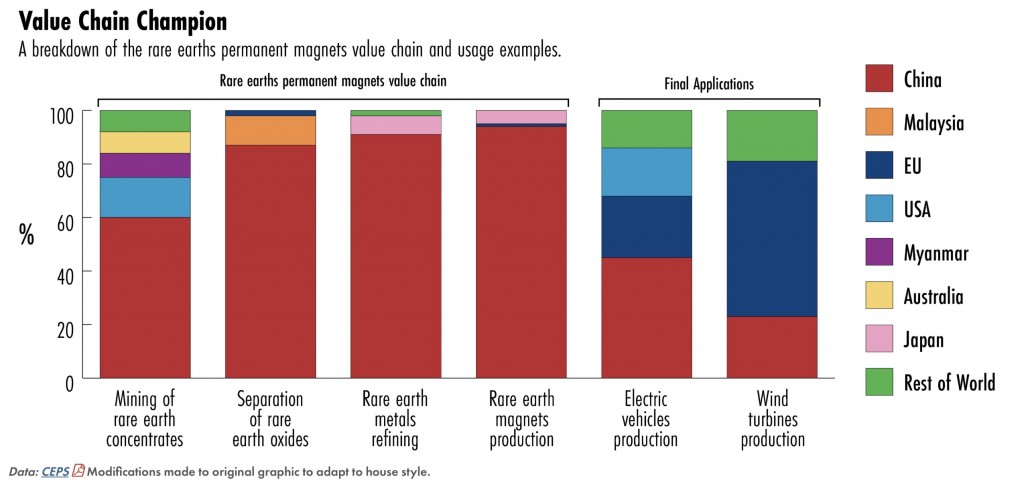

A visual of the geographical concentration of the REE permanent magnets value chain and final applications developed by the Center for European Policy Studies (CEPS) and modified by The Wire tells the story of China’s dominance:

Ultimately, Patey says:

“Reshoring, in other words, is more than just reclaiming the anchor of the supply chain. For Europe — and the U.S. — to succeed in their new critical mineral ambitions, they will need to build out links far beyond the mine.”

He adds that while these efforts are underway “[t]he elephant in the room is that, even if they all succeed, doing all these steps on European soil does not automatically make them competitive with Chinese suppliers — both on price and on tech know-how.”

Meanwhile, efforts to build mine to manufacturing supply chains for critical minerals, and especially REEs, continue to run into the “not in my backyard” challenge — an issue that continues to permeate policy discussions on this side of the Atlantic as well. As Patey phrases it, “the rare earths supply chain blends together not only challenges of national security and industrial competitiveness, but also economic and ecological welfare,” and while the newly released Critical Raw Materials Act intends to address these challenges, critical mineral extraction still faces local resistance in many parts of the regional bloc.

It is a daunting challenge; however, it is one that stakeholders – here, across the Atlantic, or elsewhere – have to tackle comprehensively and swiftly. China has already demonstrated its willingness to play politics with its resource leverage – and, as ARPN recently outlined, is gearing up to do it again as the weaponization of trade is back on the menu in U.S.-Chinese relations.