With the addition of 15 metals and minerals bringing the total number up to 50, this year’s draft updated Critical Minerals List, for which USGS just solicited public comment, is significantly longer than its predecessor.

This, as USGS notes, is largely the result of “splitting the rare earth elements and platinum group elements into individual entries rather than including them as mineral groups” – as we argued in our last post, a welcome development likely to “encourage policymakers to understand that Rare Earth and PGM deposits can and will differ in the degree to which they afford access to the full range of these key materials.”

Perhaps even more interesting, however, is the addition of Nickel and Zinc, which, as followers of ARPN may recall, puts us at two for four:

In a statement submitted during the official comment period leading up to the release of the final 2018 Critical Minerals List, ARPN’s Daniel McGroarty had called for adding Copper, Zinc, Nickel and Lead to the List.

Reviewing several scenarios outlined in the Reconfiguration of the National Defense Stockpile Report to Congress from 2009, McGroarty concluded these four metals/minerals should be added based on relevant defense criteria — and, in the case of Copper, Zinc and Nickel, based on their Gateway Metal status.

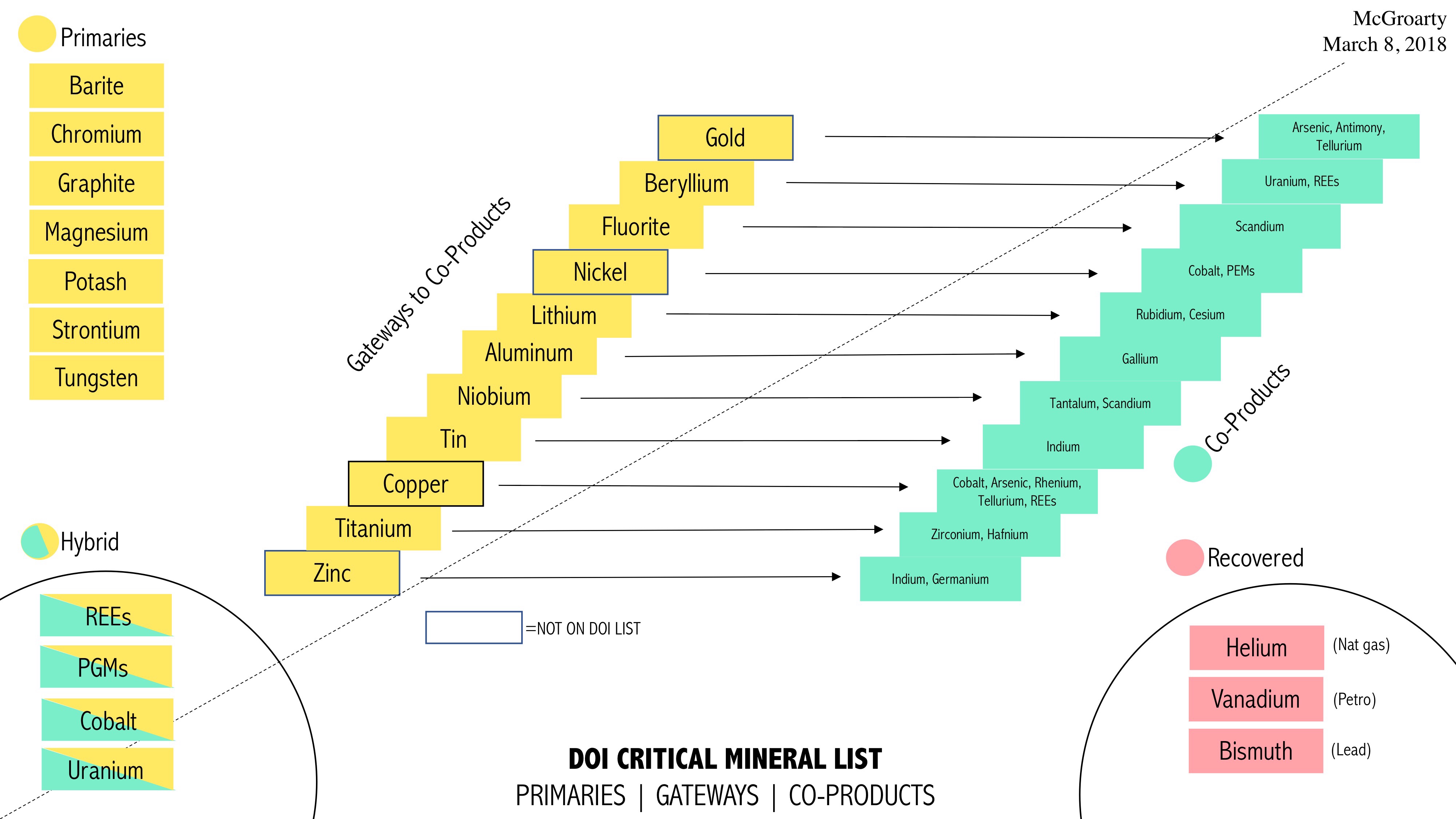

Arguing that the 2018 draft list did not convey the “relationships of various metals and minerals,” and most importantly the fact that many of them “are not mined in their own right, but obtained as ‘co-products’ of primary mining,”McGroarty pointed to the fact that Copper, Nickel, Zinc and Lead offered access to seven unique minerals deemed critical on the list, with Copper being the most versatile, since it “unlocks” five potential co-products included in the 2018 List, and submitted a graphic underscoring his point.

The U.S. Government was unmoved, making no changes to the List.

Nickel’s star has since risen.

Against the backdrop of the accelerating battery arms race, the Biden Administration, in its 100-Day Supply Chain review report released in June, acknowledged Nickel’s Critical Mineral status, noting that

“In contrast to cobalt, nickel content per battery will increase in the coming years, as R&D focused on high-nickel in cathodes has shown significant and accelerated commercial adoption. The potential shortfall from this increase in demand poses a supply chain risk for battery manufacturing globally, not just in the United States; given the pervasive need, the established nickel industry is ramping up production and processing, and the United States is falling further behind China in this critical material.”

The Department of Energy-led chapter of the 100 Day Report further concluded that “If there are opportunities for the US to target one part of the battery supply chain, this would likely be the most critical to provide short- and medium-term supply chain stability,” noting the urgent need to develop a strategic framework for securing Class 1 nickel. As we commented at the time, no other “non-Critical” received more mentions in the White House report than Nickel.

Add in the fact that Nickel provides Gateway access to Cobalt and the PGMs, and the case for including Nickel into the 2021 Critical Minerals list just got even more compelling.

Zinc, primarily used in metallurgical applications, is also a Gateway metal, yielding access to “Criticals” Indium and Germanium, is also seeing greater application in green energy technology, and, according to Mining Weekly the “increasing concentration of global mine and smelter production and the continued refinement, as well as the development, of the quantitative evaluation criteria” put zinc above the threshold for inclusion.

If Nickel and Zinc are ARPN’s two “hits,” we still stand by our two remaining “misses:” Copper and Lead.

Less flashy than some of its tech metal peers, Copper’s traditional uses, new applications and Gateway Metal status make it highly versatile.

Copper is an irreplaceable component for advanced energy technology, ranging from EVs over wind turbines and solar panels to the electric grid. The manufacturing process for EVs requires four times more Copper than gas powered vehicles, and the expansion of electricity networks will lead to more than doubled Copper demand for grid lines, according to the IEA.

Add in Copper’s Gateway Metal status and a 2019 mining executive’s projection that “[t]he world will need the same amount of copper over the next 25 years that it has produced in the past 500 years if it is to meet global demand.” The just-passed federal infrastructure package and recent announcements of new EV goals and fuel efficiency standards — will only add to the outlined Copper demand scenarios.

Meanwhile, Lead continues to be a key ingredient in battery technology, with the lead-acid battery industry accounting for about 92% of reported U.S. lead consumption during 2020. On the Co-Product front, Lead is Gateway to two “Criticals,” Arsenic and Bismuth.

While the rationale for including Copper (and to a lesser extent Lead) into the latest iteration of the U.S. Government’s Critical Minerals List remains strong, and is perhaps, in the case of Copper, stronger than ever, we choose to see the glass as half-full, and are encouraged by the inclusion of Nickel and Zinc — testament to the fact that policy makers and other stakeholders are increasingly acknowledging the challenges associated with providing reliable supplies of the Critical Minerals underpinning our “Tech Metal Era.”