2024 marks the 75th anniversary of the NATO alliance, a transatlantic partnership and security alliance that has played a key role in the global security landscape over the last seven decades.

Against the backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and an increasingly volatile geopolitical environment, experts argue that the alliance appears to have found a “new lease of life,” with a broadened agenda that “now even includes critical infrastructure protection and climate security.” However, there are a number of structural challenges that will need to be addressed for NATO to operate efficiently in the current context and successfully navigate crises as tensions around the globe continue to flare.

Writing for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Gregory Wischer zeroes in on the importance of critical mineral supply chains to sustain the alliance’s (and member states’) defense industrial bases and thus military power.

Wischer outlines minerals have always played an important role in this context.

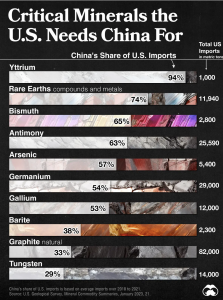

While supply chain challenges are not new – Wischer points to increased manufacturing of bullets and artillery shells causing supply issues for copper and overall increased defense production triggering shortages of manganese, nickel tin and zinc during World War II– the U.S. (and in the post-WWII context the U.S. and NATO) used to navigate these waters from an overall position of strength with strong domestic or intra-alliance production and significant stockpiling of key materials. Fast-forward to today, stockpiles are depleted, and the U.S. and its allies rely on defense industrial bases with severe vulnerabilities, largely in light of an over-reliance on imports to critical minerals from adversary nations like China, key supplier of graphite, REEs and other battery materials, and Russia, from where much of the world’s aluminum, nickel and titanium are sourced. (see Figure 1 in the piece for a great visual historical perspective)

Writes Wischer:

“Mineral supply chain risks are rising as the adoption of renewable energy technology increases mineral demand and as the rearmament efforts of the U.S. and allied militaries in support of Ukraine use more minerals. Coupled with limited production and stockpiles, the U.S. and other NATO militaries face three serious risks that could lead to mineral shortages: foreign export controls [see ARPN’s coverage on export controls here]; rising military demand amid great power competition, including the possibility of a U.S.-China conflict; and disrupted sea-lanes. The United States and other NATO countries must act now to address these supply chain risks.”

Wischer suggests that to successfully address the challenges ahead, the U.S. and other NATO members should:

- increase their mineral stockpiles, prioritizing minerals used by their militaries,

- expand their efforts to increase domestic mining and recycling of minerals,

- prioritize friendshoring production for minerals with limited domestic reserves,

- consider mineral substitution and rationing to alleviate the pressure on the production of certain minerals.

There are other key structural challenges NATO faces at 75 that are worth discussing, but with the U.S. and NATO allies supporting Ukraine and Israel as tensions over the Taiwan Strait continue to flare, the time to take assertive steps to strengthen the supply chains for the metals and minerals underpinning the security of transatlantic alliance is now.

ARPN will be taking a closer look at several key minerals, steps taken to bolster critical mineral resource security particularly for the military and associated challenges in a forthcoming post later this week.